The material presented here is part of an ongoing artist's inquiry into rural emancipatory movements and their transnational relationships during colonial modernity. So far, the research has delved into a history of peripheries among Ireland, West Bengal, the South of England, North China, Nova Scotia, and Tennessee ca. 1890–1940.

There are currently twenty images in the slide show.

Hover to stop the images from sliding further.

Move your cursor away for the images to continue.

↓

Roughly between 1890 and 1940, there emerged a worldwide movement for modernization in the countryside. At this time, modernity had largely taken hold in industrialized urban

centers of production, on transportation routes and hubs for logistics, but rural areas across the globe were exploited to bear a massive amount of the costs by providing the

resources for the increased growth without seeing any benefit – and without being seen.

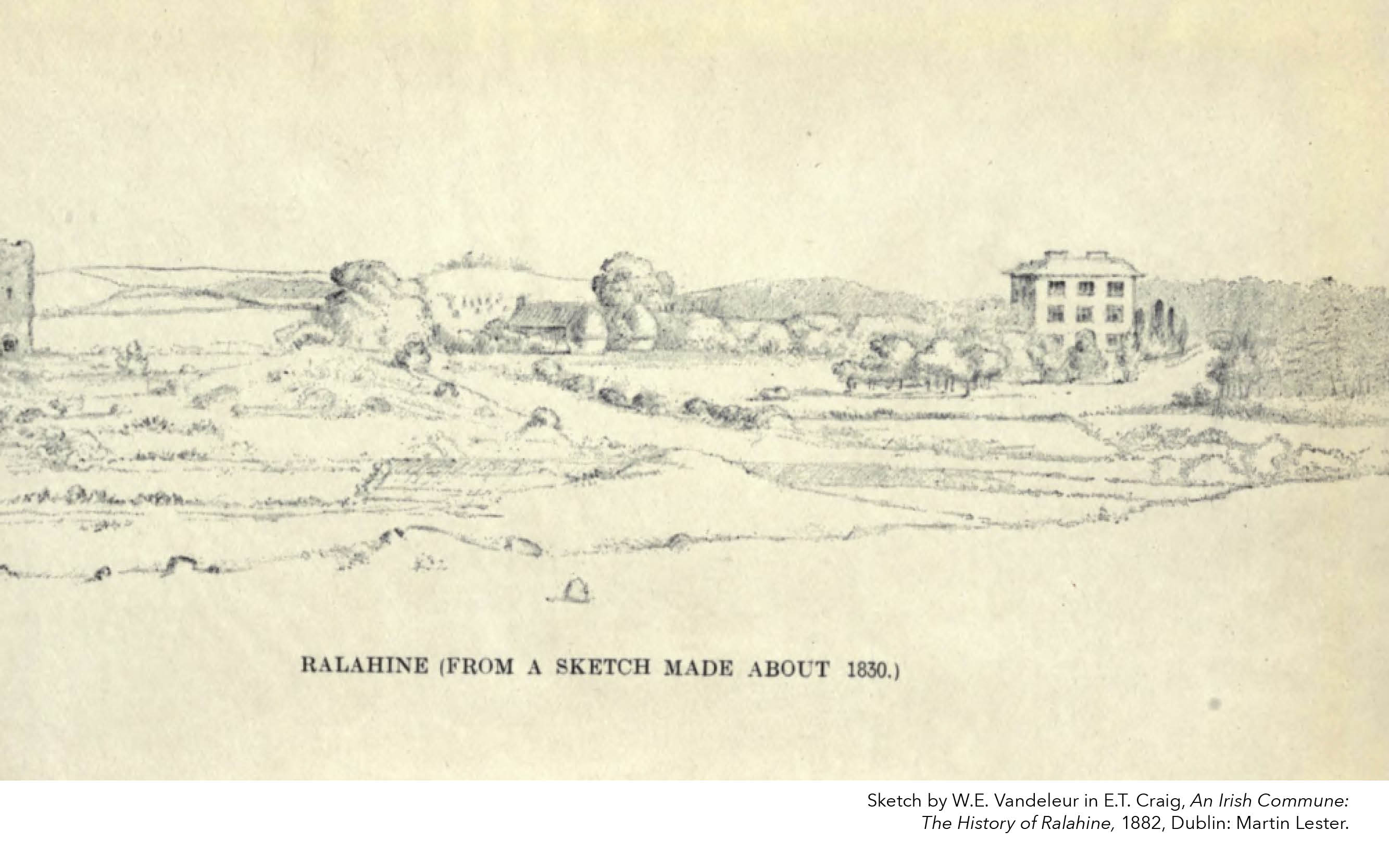

For the rural reform work of this period, the term ‘rural reconstruction’ was coined in Ireland in the 1890s, based on the earlier rebuilding of the Southern United States after the civil war.

The general historical period is also called ‘colonial modernity’ as it constituted a high point of European and North American extractive imperialism across the planet.

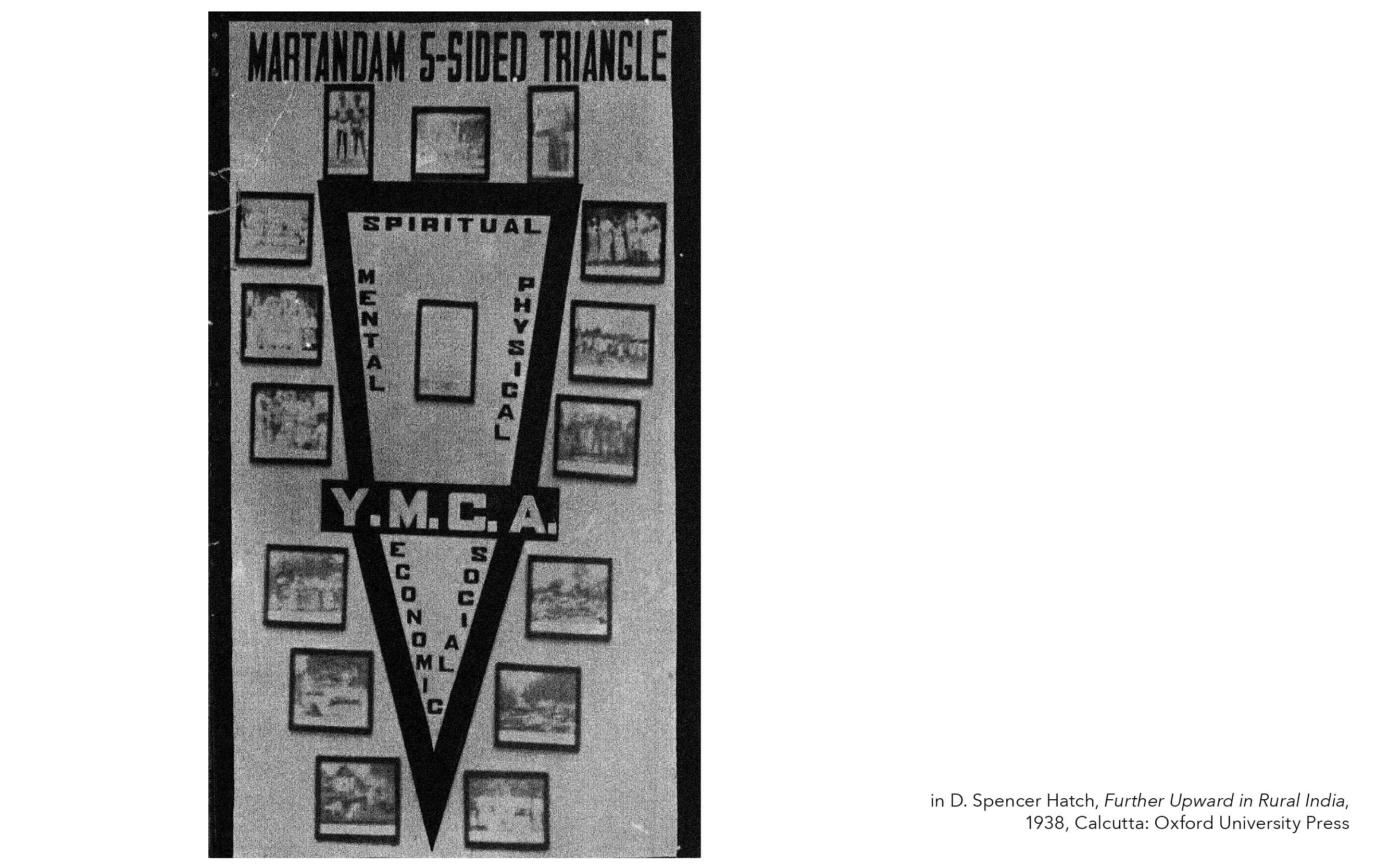

Not all rural reconstruction work was imposed from above in the shape of large-scale projects, for instance by state governments, philanthropic organizations, or the church. Alternative and specifically

local modernities were forged in a number of places by small emancipatory groups. Some of these movements were long lasting. They were often organized by cosmopolitan intellectuals who stood in

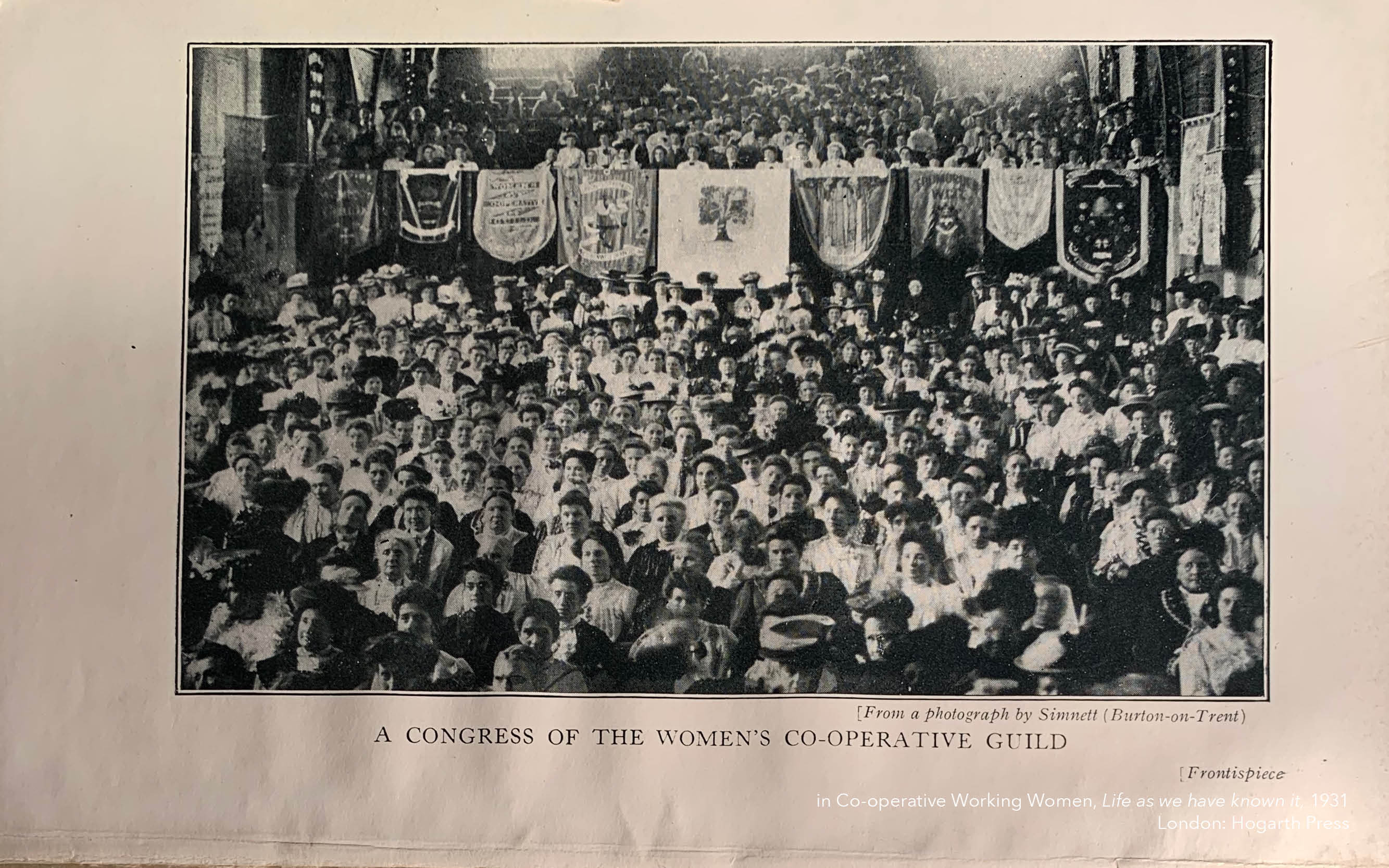

exchange with each other in a transnational network that formed around the notion of co-operation. The internationalism and pragmatic idealism of the co-operative movement at the turn of the century

was central to this network of local rural reform. In the beginning of the 20th century, co-operation was still considered a third way forward next to communism and capitalism – the latter two became

the more well-known ones in the course of the Cold War. Illustrating the power of this movement, the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) was one of the only internationally

organized groups to survive the First World War. It was independent, pacifist, and outspoken in its opposition to the war.

The Wall, a theatre play for children written by British reformer Margaret Digby in 1925 for London rallies of the Labour Party, provides an understanding of the ideology of

co-operation and international solidarity at the time.

Lev Tolstoy‘s Christian anarchism, Pyotr Kropotkin‘s evolutionary principle of mutual aid, John Dewey‘s educational philosophy, Yoguslavian health co-operatives, and the Danish adult education

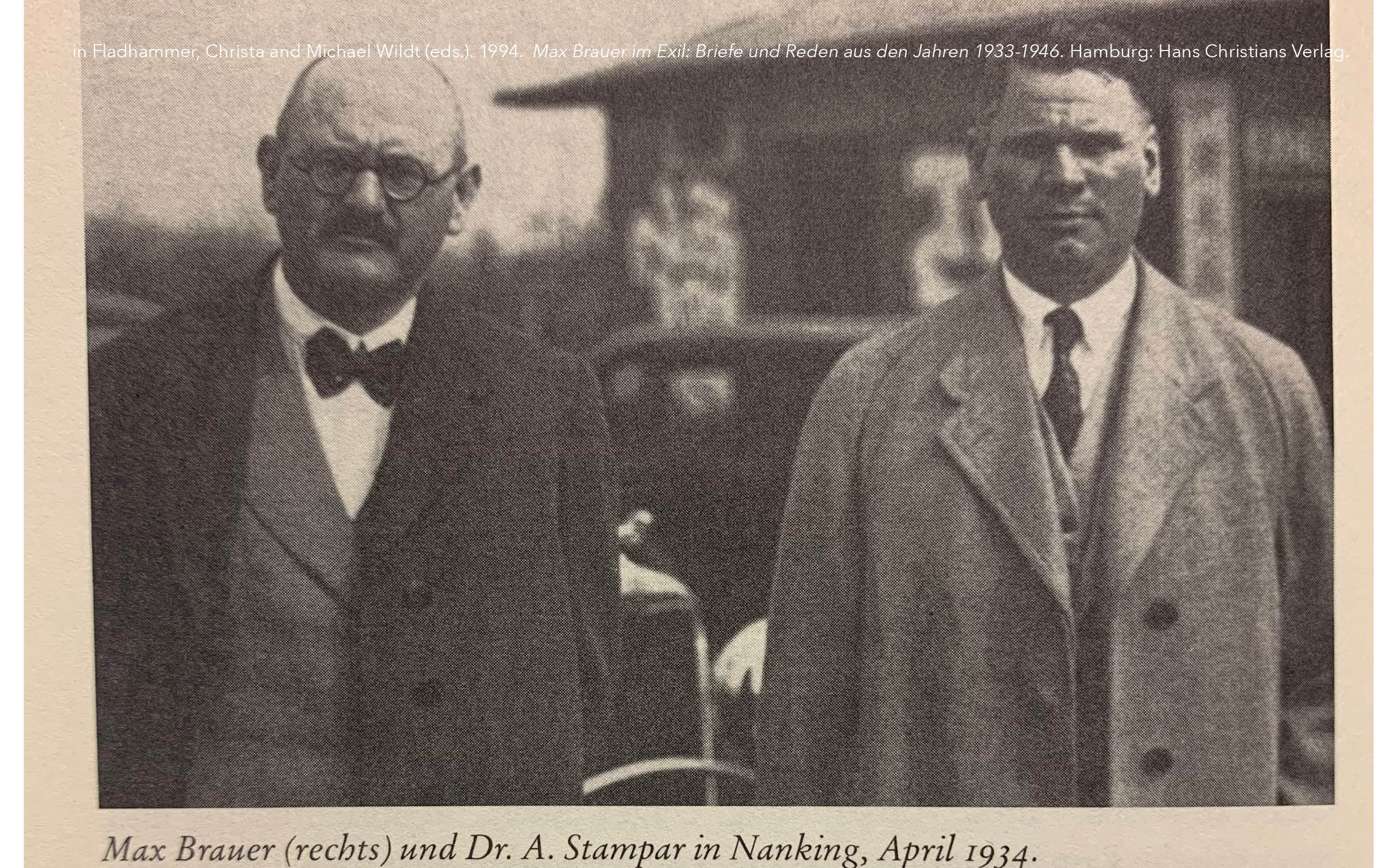

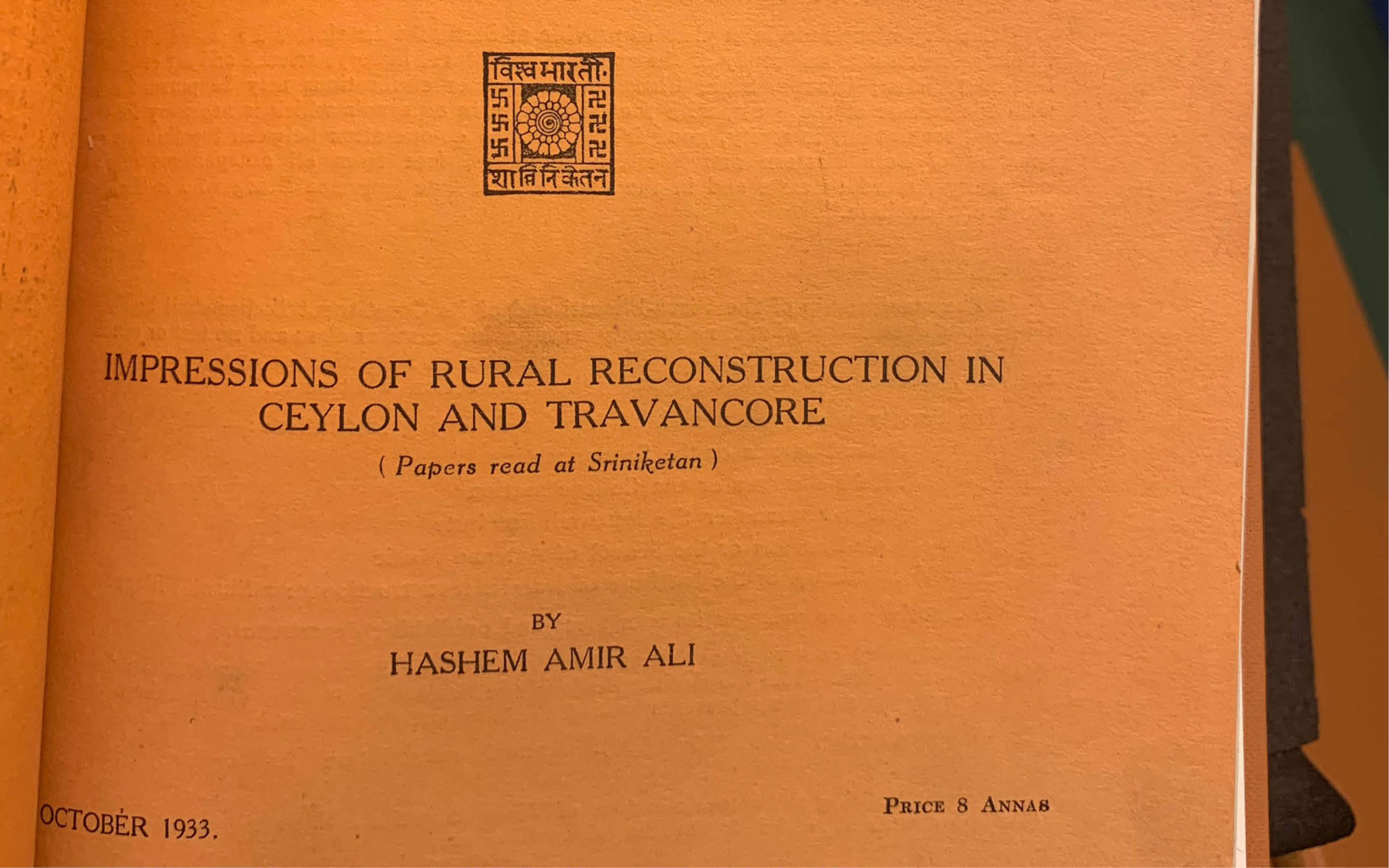

center: reformers around the world shared similar references for their strategies of rural reconstruction. Intensely entangled on various levels, from purely local organizing to the massive projects of

nation-states, reformers exchanged transnationally and, through their work, negotiated the limits of modernization from above. Raiffeisen‘s Self-help Societies for Farmers are one of the earliest modern

emancipation movements in the countryside (from around 1850). As an international model they were just as important as the Danish folk school system.

They also impressed the Plunkett Foundation, an Irish organization that helped rural co-operatives share information around the world. Its founder Horace Plunkett helped spark and sustain the

Irish Rural Reconstruction Movement from 1890. The cosmopolitan feminist reformer Margaret Digby became the driving force behind the Plunkett Foundation for decades after it moved to England in 1925.

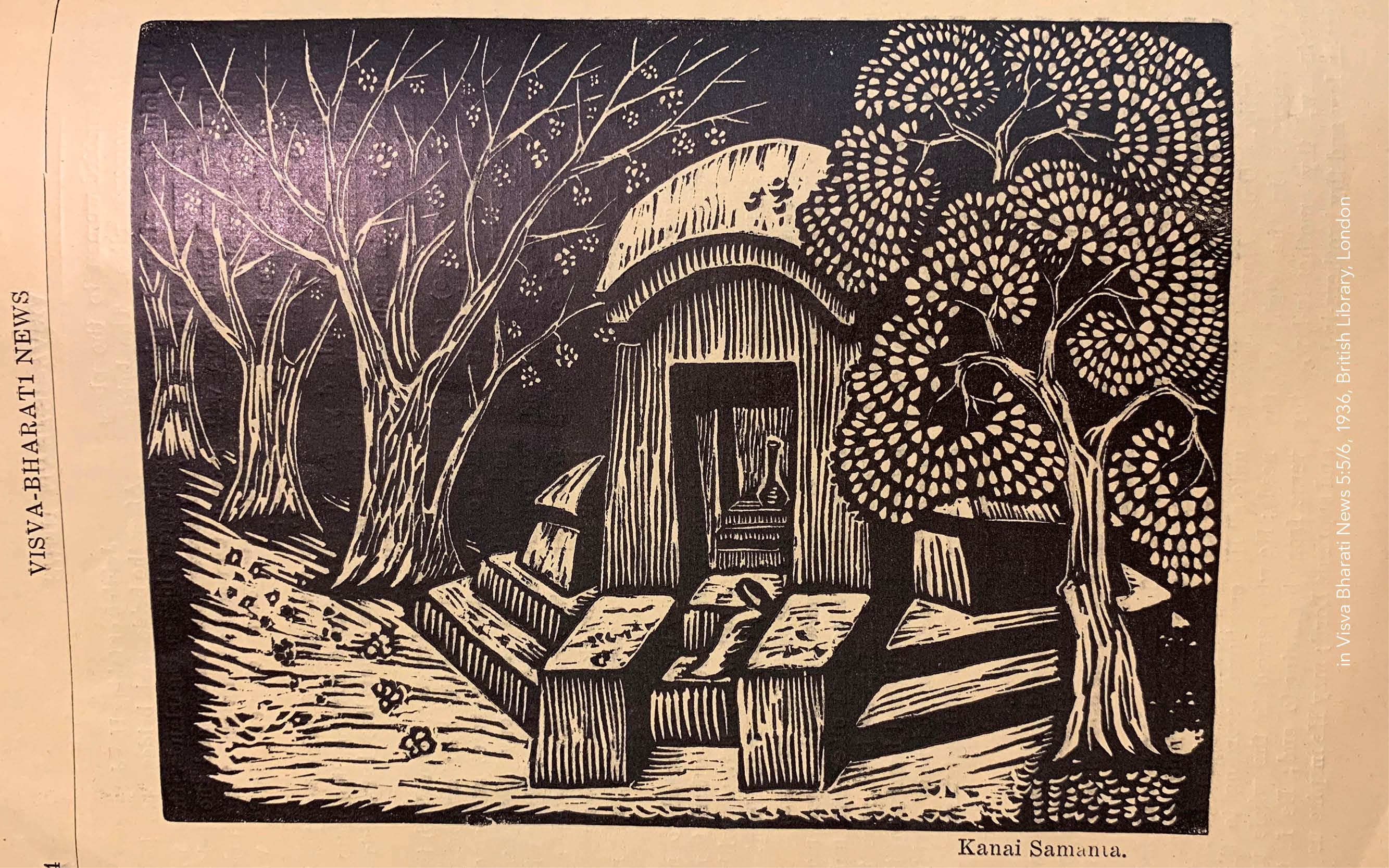

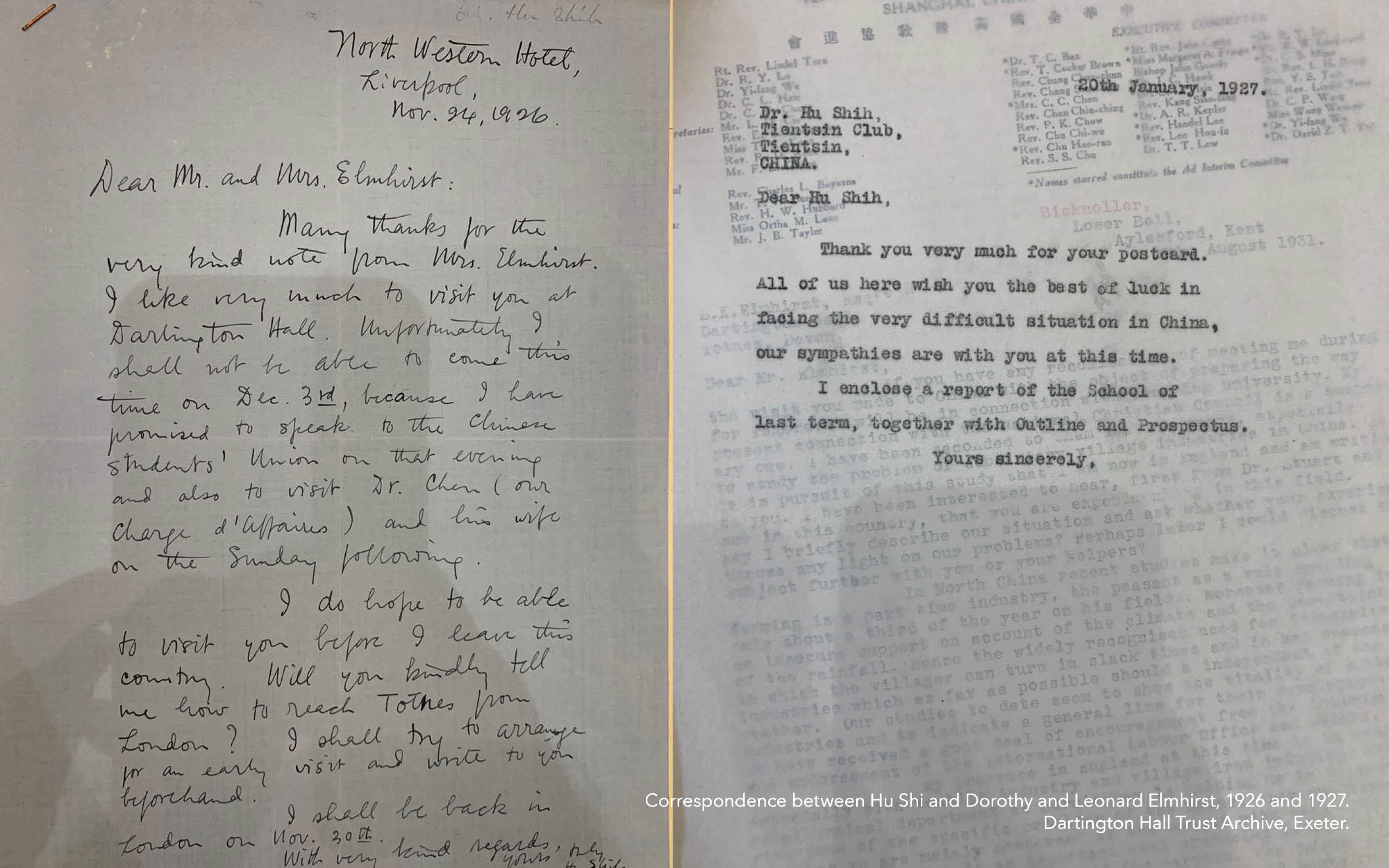

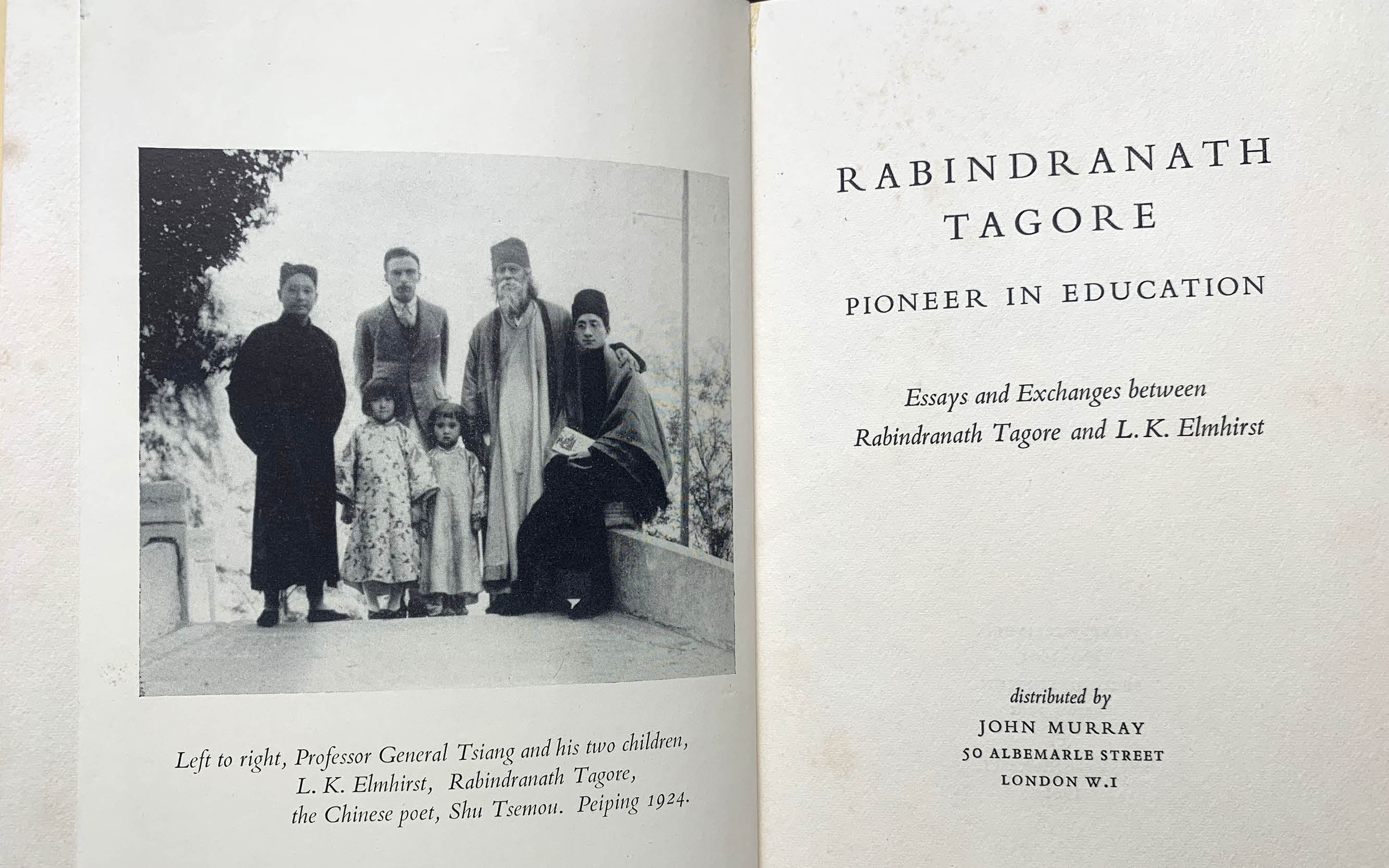

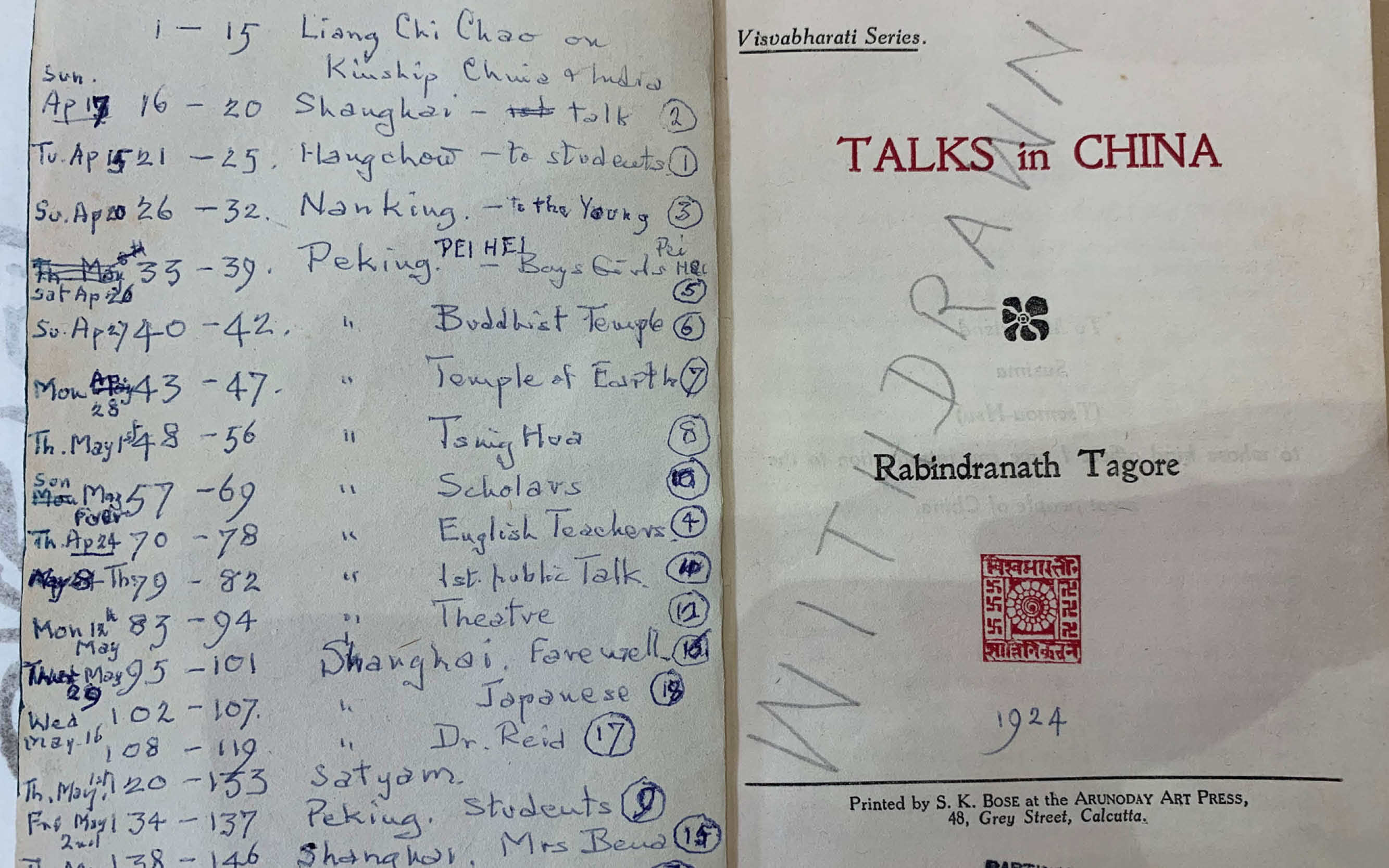

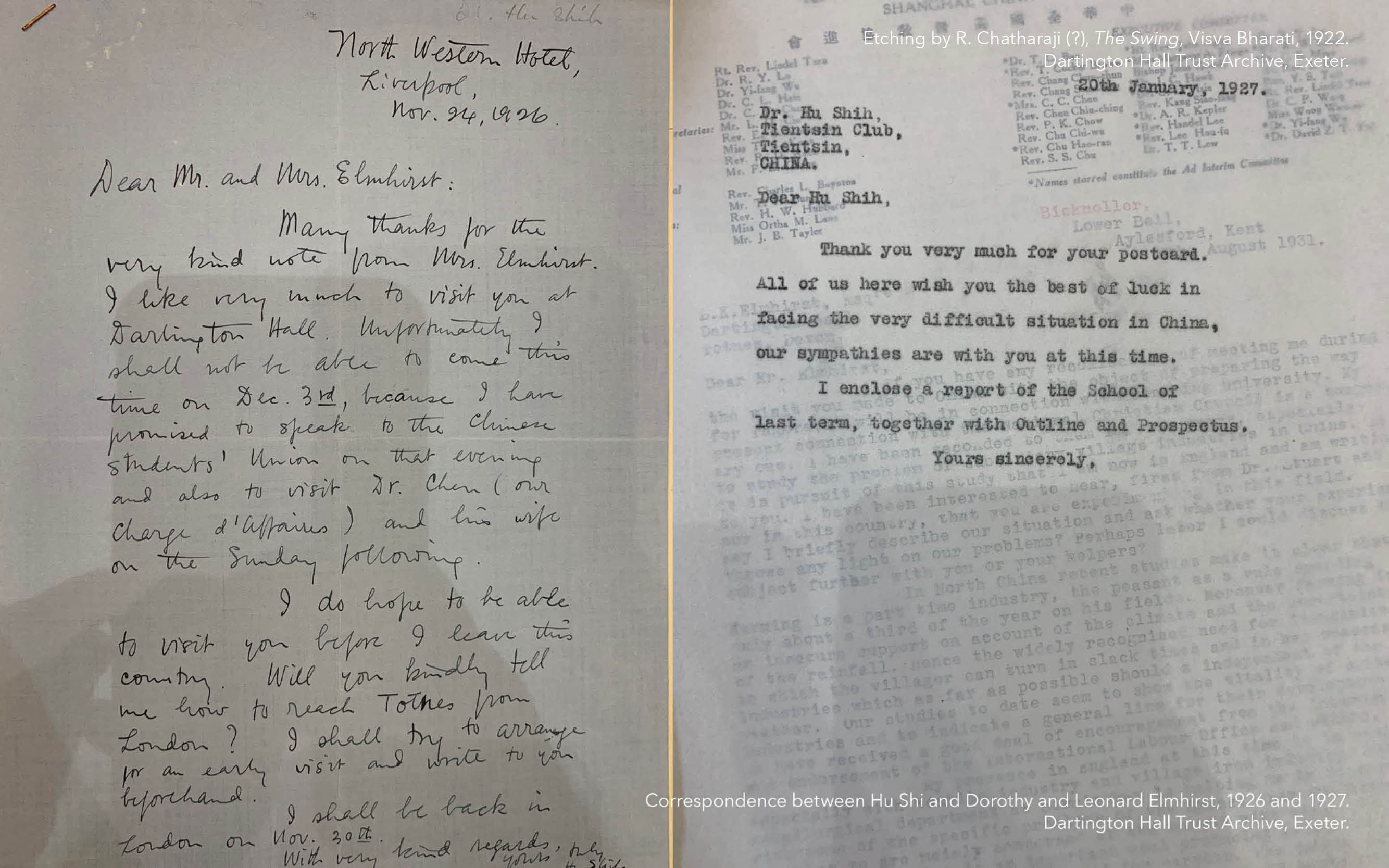

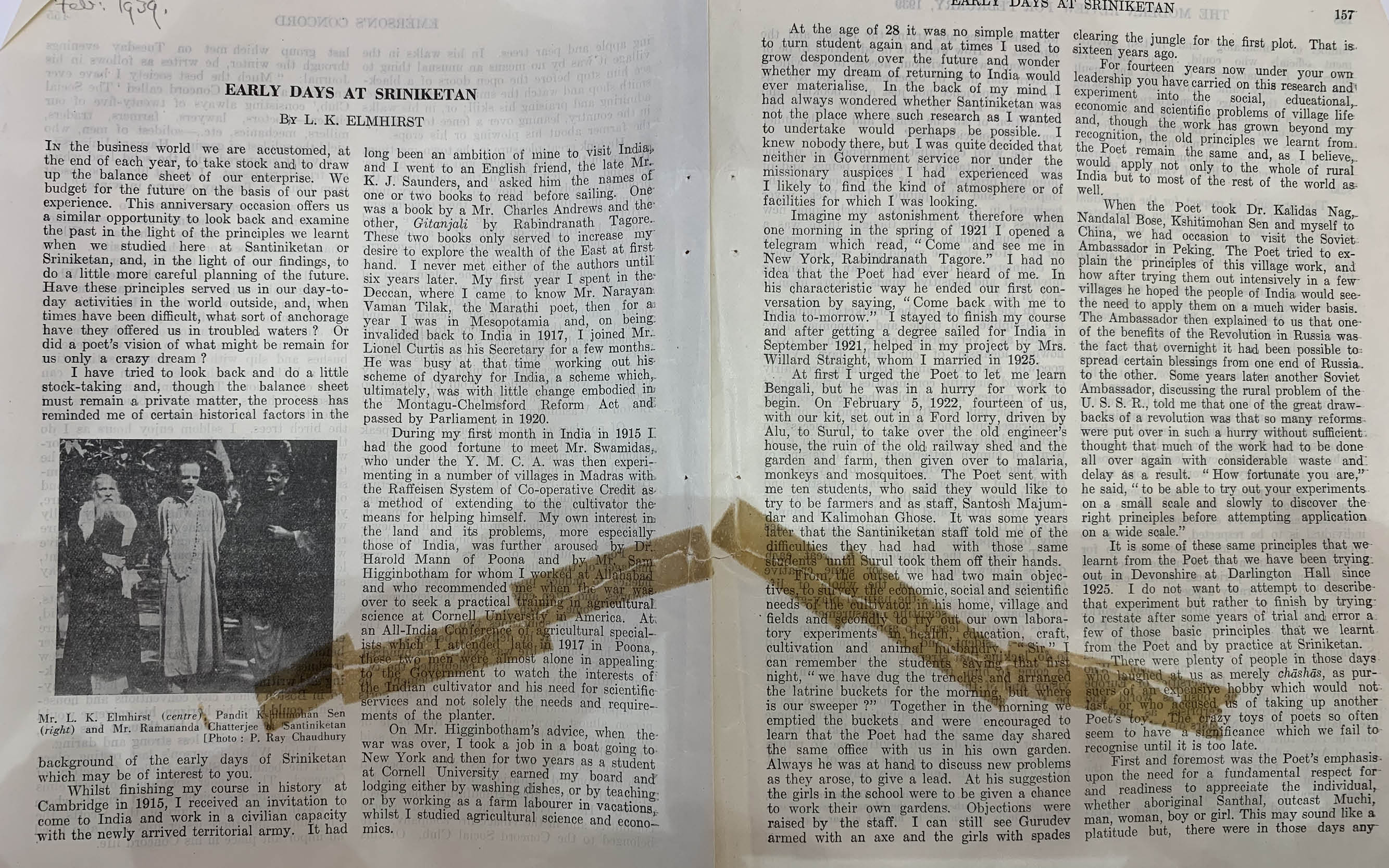

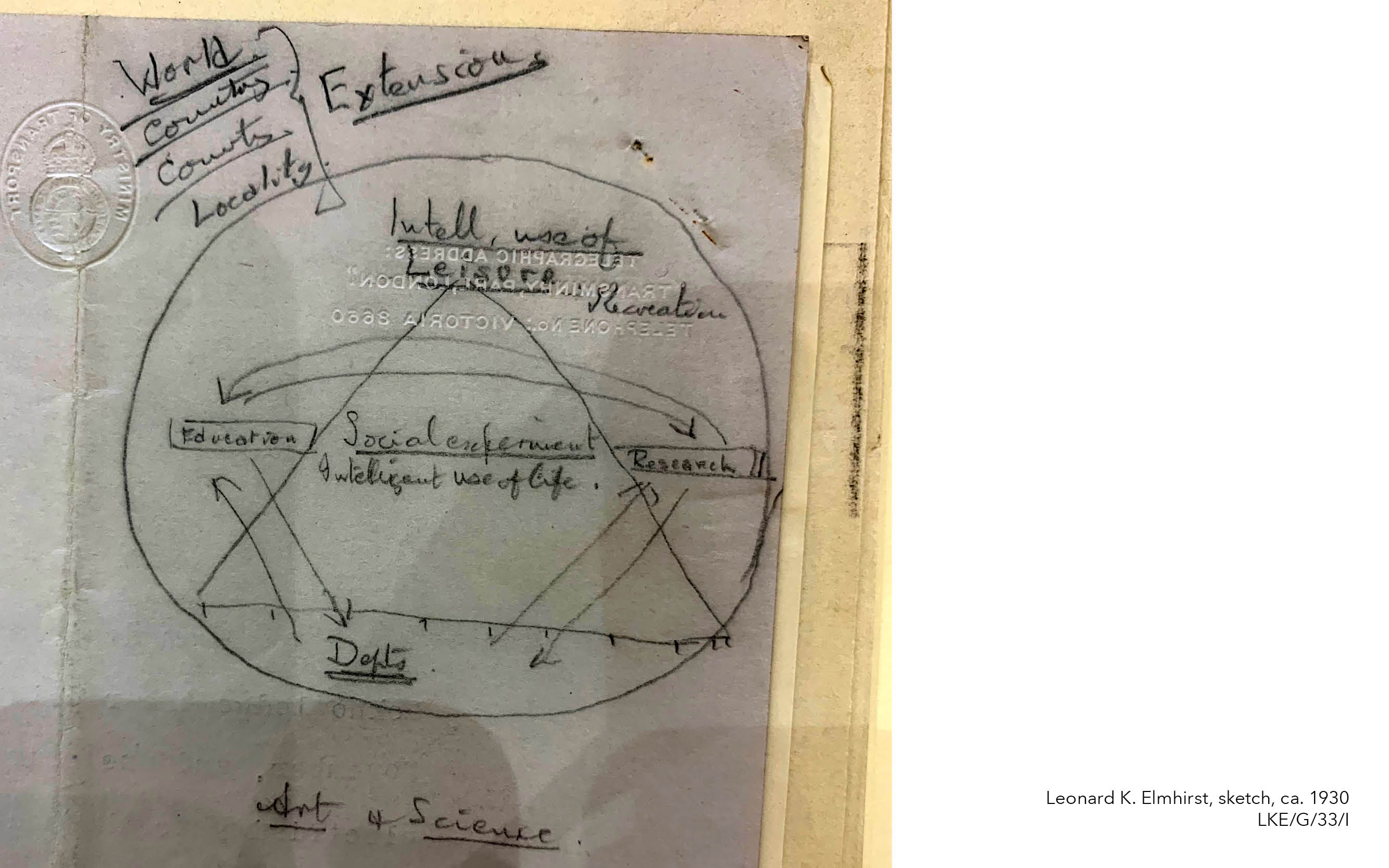

Briton Leonard Elmhirst visited the Foundation‘s Reference Library in Dublin in 1921, shortly before he was recruited to West Bengal by poet and reformer Rabindranath Tagore to work there for three

years supporting the founding of the village project Sriniketan which complements Tagore‘s Visva-Bharati University to this day. In turn, Elmhirst and his partner Dorothy White founded a reform estate

in the south of England in 1924 called Dartington Hall. That was eleven years before Myles Horton‘s Highlander Folk School was founded in Tennessee, an egalitarian, anti-racist initiative in adult

education which became known not least as the alma mater of civil rights activists like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King. It was not far from Black Mountain College which started the following year.

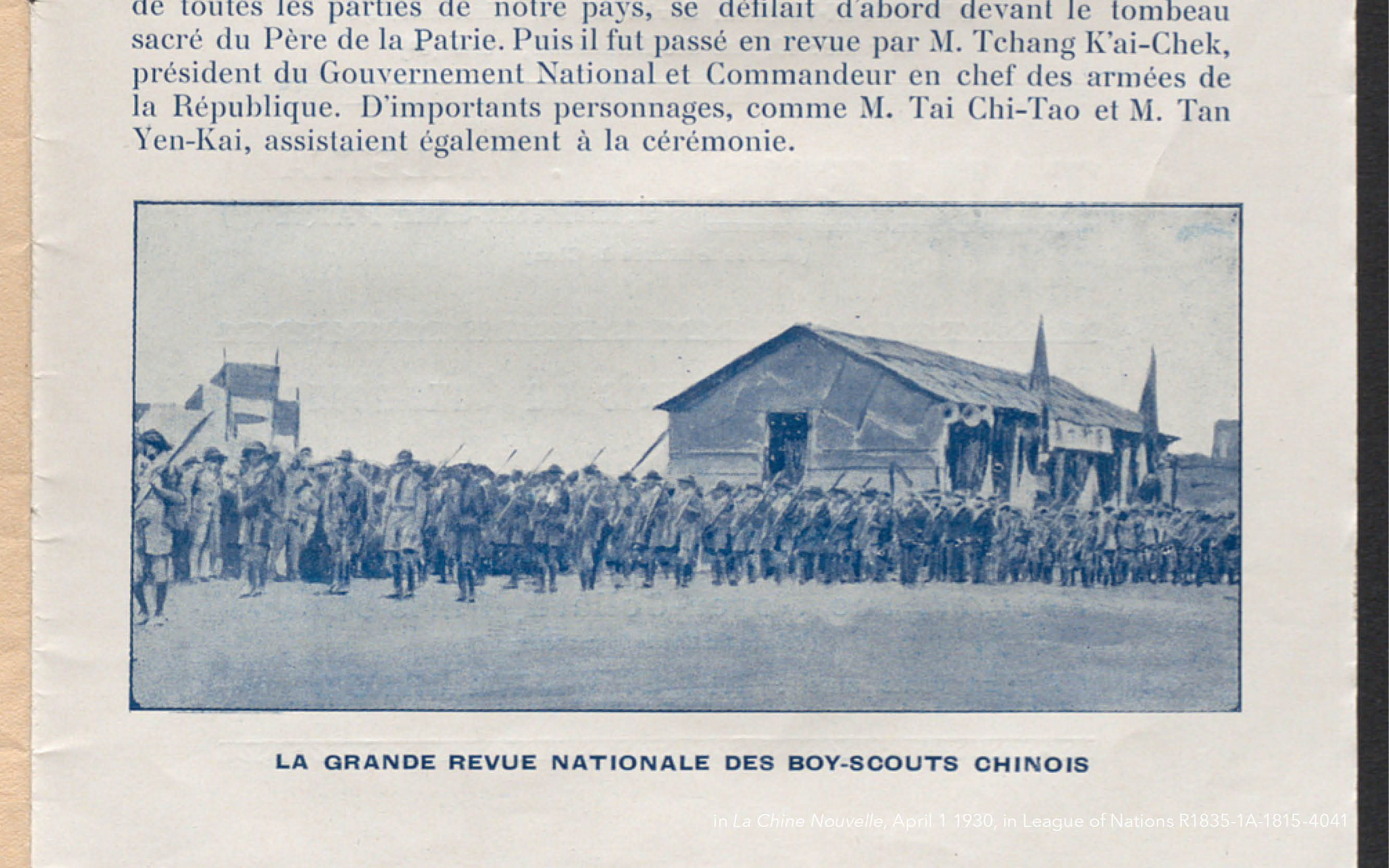

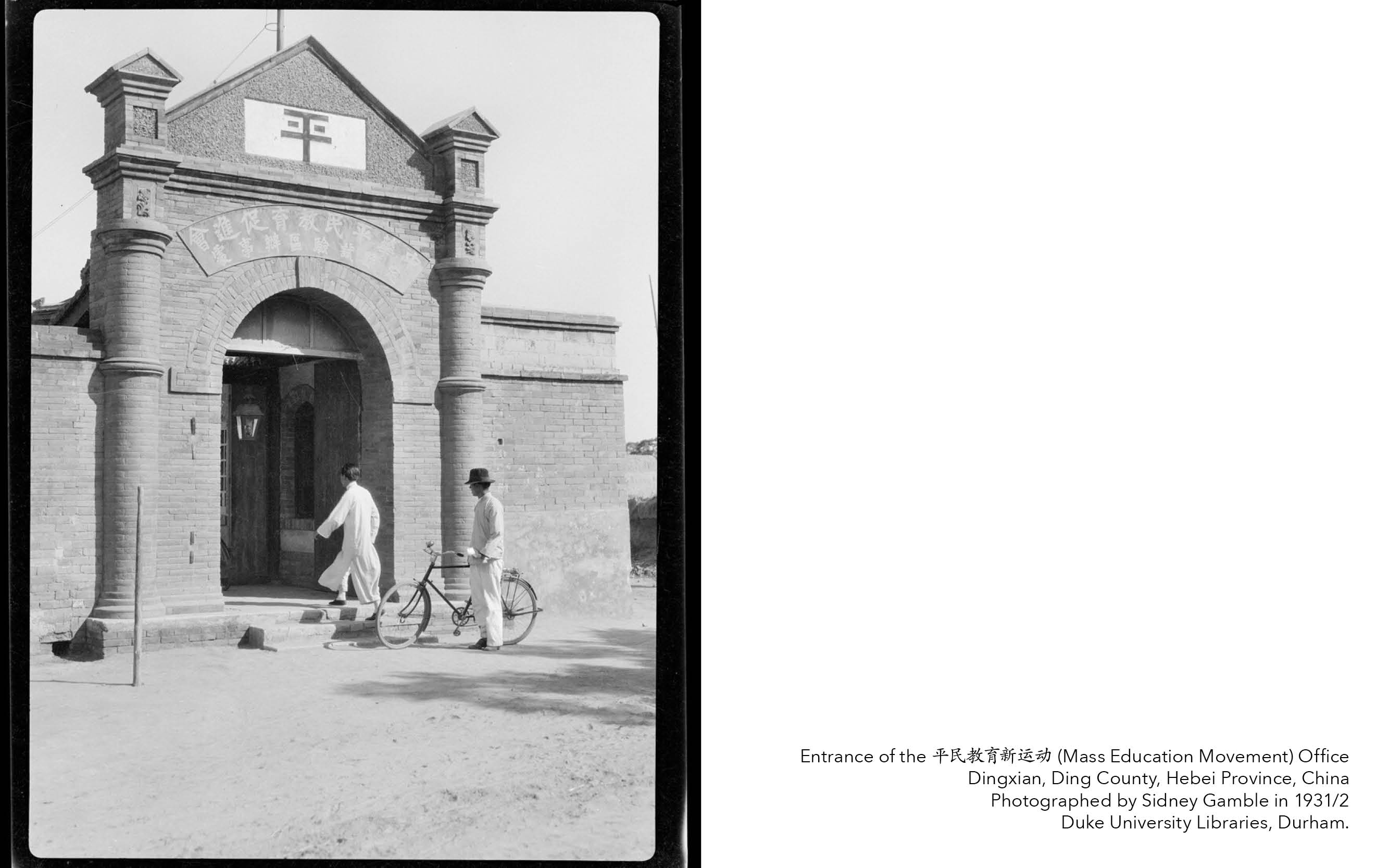

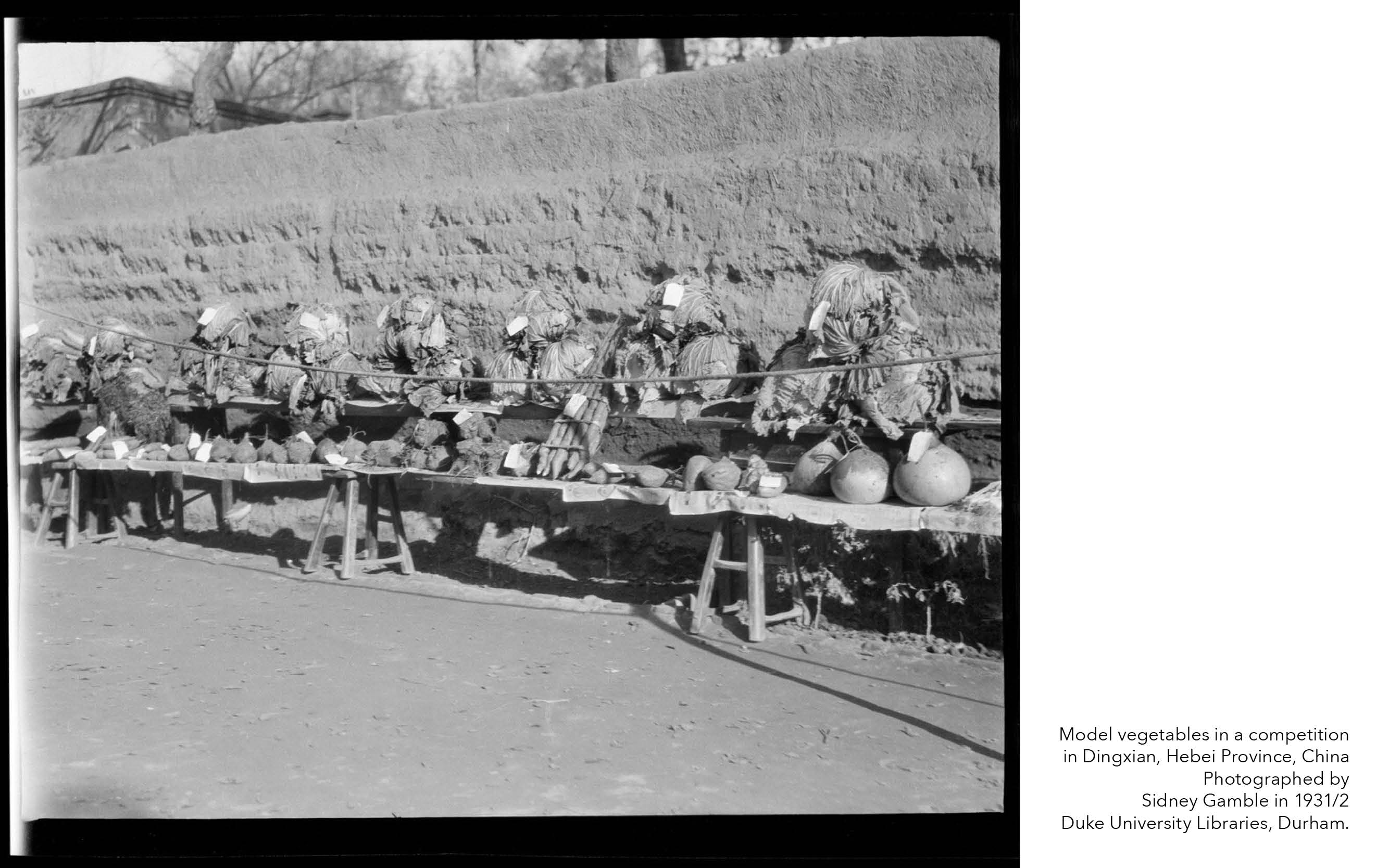

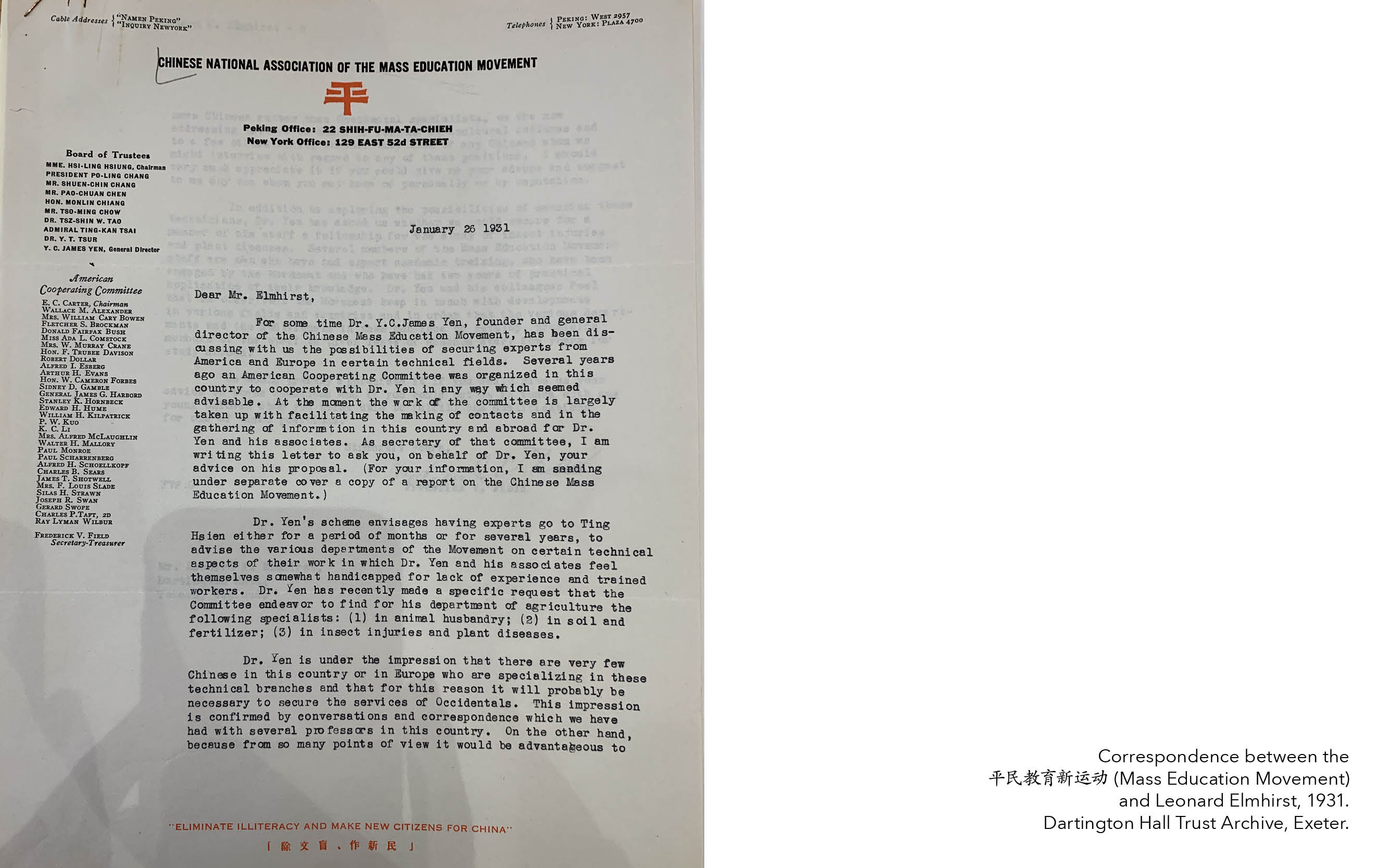

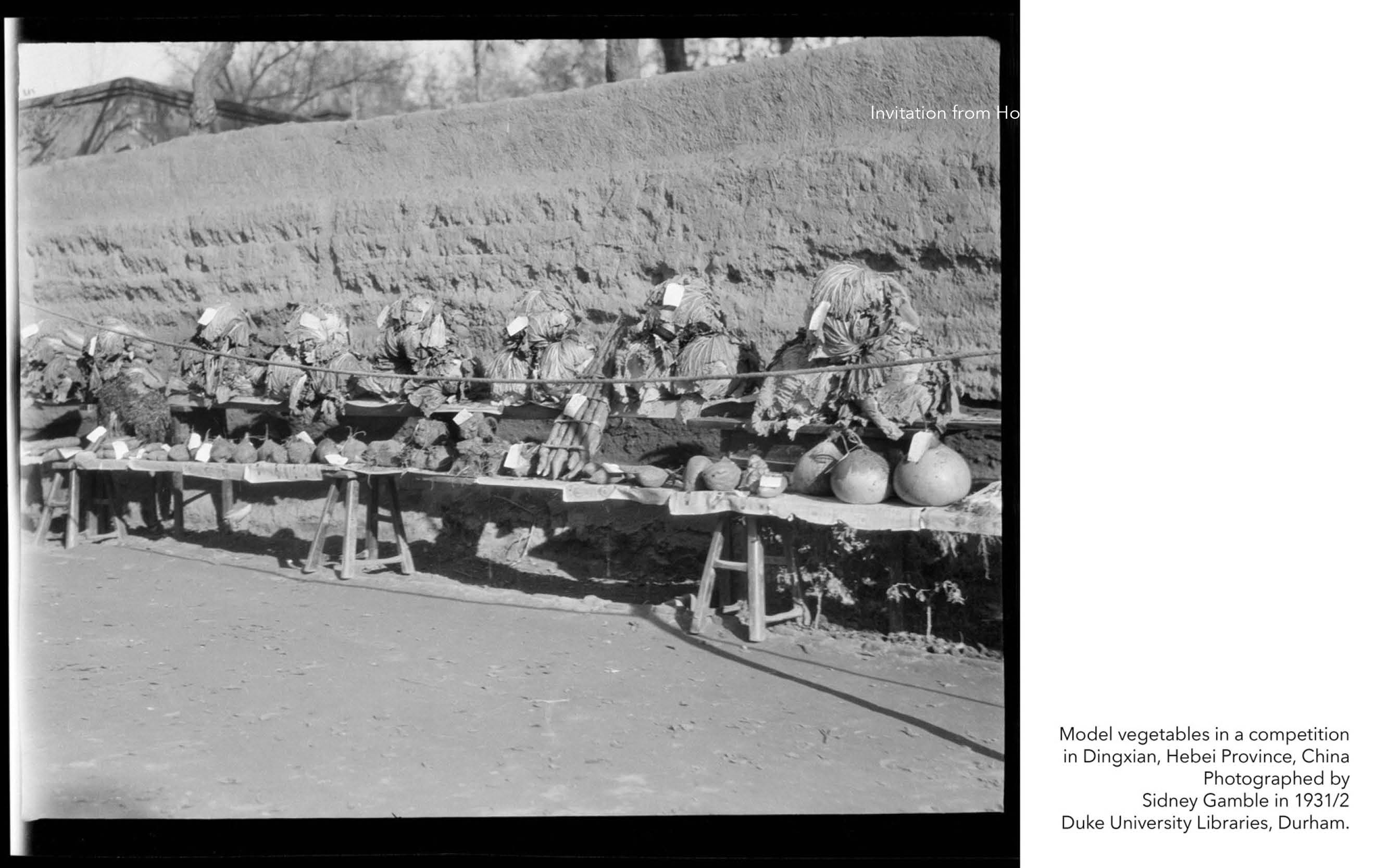

At the same time, the Antigonish Movement in Nova Scotia in eastern Canada came into full swing, starting from the University of St. Francis Xavier. Already in 1926 the Chinese Mass Education Movement

(平民教育新运动 pingmin jiaoyu xin yundong) of Y.C. James Yen (晏阳初 Yan Yangchu) went rural in Ding Xian in northern China for a decades-long practice of situated village self-empowerment. After the

Second World War the organization moved to the Philippines and since then has provided alternative tools to western developmental aid to many agents of the Global South.

The exchange of these reformers was enabled to take place owing also to new organizations such as the International Co-operative Association, the Workers International Relief, and the League of

Nations. While the modern homogenizing agenda of these institutions tended to run counter to reformers’ work they had to negotiate funders' expectations and often redirected the resources offered smartly

in order to do their work at all.

Titles are in chronological thematic order.

I encourage you to browse and learn more.

Hover over a title to see if there is a digital open source.

↓

Colleagues get together and we talk about the past. When we talk about the past, we are really discussing where we are at now. The present is messy.

Only as it moves past us, does it enter sedimentation. To work in the past is to re-member selected memories into the fabric of our living realms.

Memories are uncovered and connected, lost, invented, tarnished and altered and buried and rescued. We like to picture them situated in a consistent time-spatial continuum.

And yet, in the very act of coming up with the past, we create a diachronic relation within our present rather than fully locating a prismatic memory in a historical,

past present – an impossible quest.

I find that we are both lucky and tragic, facing an overwhelming amount of relatively well-catalogued records of the most recent past. That is, if we want to dig back into

primary history through such time-travelling documents as letters and notes and reports and files and recordings and conversations instead of simply consuming an account that's already

been digested by someone else, for example an historian.

If we're in the business of such time-travelling, we insert ourselves in a past messy-present. It's a chance to unbury something new to ponder, but it's also easy to get lost in

the sea that is the formal and informal archives of our world.

Almost three years ago, I fell into such a warp in time, and have been swimming in past tidings ever since. You ask what my inquiry has to do with our present, and

our future, and sometimes I forget myself that the simple reason why I went swimming in the first place is that I could relate so immediately to what was there.

A hundred, hundred fifty years ago, there were people in many places on the planet dealing with the same questions that continue to bug the world today – and will continue to worry it just

as much in the foreseeable future as they did then. This shouldn't come as a surprise.

The modern vision of final solutions and linear progress underlying the story of our Eurocentric colouring is nothing more than that; a myth. Instead, I think, to make the world a live-able

place for all, for Earth-ages to come, is going to take continuous work; 'staying with the trouble' as Donna Haraway writes. As we're seeing in the present, 'modern democracy' is not a vaccine

that, once humans ingest it, cannot go away anymore. That narrative is part of the myth of progress. The real thing keeps taking attention, devotion, political education; it is really inconvenient.

And really, the vision of an end of time when all that can be achieved has been achieved sounds like a sort of death to me. I am in a relationship with the past because of the real,

laboursome future.

Now, I am not a historian. Am not in the business of controlling big narratives; am neither looking for the past in pursuit of fulfilling a nostalgic sentiment nor of

producing an authoritative, singular account.

Still, the reasons for my remembering are equally suspect. I have to admit that I can appreciate the idea of working with history, of sorting, imploding, rephrasing, misunderstanding,

imagining. Of listening and nurturing and supporting it. With this kind of work it is necessary to provide a disclaimer of fiction.

Again, my motivation for historical research is ultimately that I care for and about the future. So rather than collapsing time to deceive under the tricky cover of 'truth,' or to cleanly

extract resources from the archive, I am looking to open diachronic portals. Messy portals that make the present equally vulnerable to be affected by past agency. In the best case, this means

learning and changing with the past.

To be open to change – a future that will be specific and unique and part of an infinite texture of the world as it continues to emerge (I think it will do so sideways) –

means being open to do the work; long-term; selflessly, to some extent. The people of the past whom I meet in archives, libraries, and oral histories were doing just that. As such they

are my kin and my kin's kin, and there is much we have to talk about right here and now. Perhaps what I am thinking about is that it is necessary to choose a legacy to become from, and

to deal with the legacies we cannot choose the way I would try to cope with a trauma.

In order to imagine a future, the narrative emerging from this my work of history needs to move between times. This future needs to present an alternative to utopia and dystopia.

That alternative may yet be fictional, but is of a real and urgent fabric.

I want to go into more detail on the idea of utopia because to address local histories that were part of the large, complex, future-identifying transformation called modernity comes with

a lot of baggage which I believe needs to be accounted for.

Utopian thought rose to popularity alongside the invention of the future in early modernity, as a sort of technocratic paradise-substitute. It promoted the idea of universal solutions

that could end problems of humanity once and for all. It was symptomatic of other 'total' ideas of the time, such as complete control over the environment by human technology (framing 'Nature'

as an adversary). High-modernist projects like the building of national dams did not try to localize but to decontextualize because they were conceived on a mass scale, based on the example

of emerging mass fabrication, for which the global imperialist extraction of resources, human and otherwise, became the overarching premise.

Decontextualization remains a major colonizing strategy today. It is embedded in the modern credo of linear progress which states that, provided the right recipe is found, one day the

work will end and tranquility can set in. Utopian thought like this is heavily indebted to Christian culture which lures believers with the event of the Last Judgement and the Apocalypse – and

Heaven for those who have earned grace. In this myth, each person is responsible for accumulating cosmological credit enough to enter themselves. The liberal myth for the individual – promising that hard

work leads to corresponding harvest (and those who do not get to reap must have done something wrong) – follows suit with this apocalyptic promise just as much as the larger modern narrative of

historical progress. They do not account for the fact that most of us have no choice but to work hard anyway, no matter if we see it bearing any fruit in our lifetimes or not.

At this point the story about the churn we're in, which we've told ourselves for many, many decades, makes it seem desirable to follow suit with a system that presents itself as inevitable. As

inevitable as the ultimate victory of democratic political systems. As if there was something to achieve if we only exploited ourselves enough.

Exploiting what we find in the past in disregard of the situatedness and context of those ideas can only reproduce the same oppressive, hierarchical system of vague and empty promises.

For me it is this ideology of progress with all its cruel implications, pervasive in the period of my research and still fundamental to Eurocentric thinking today, which needs to be taken

into account when I'm time-travelling.

But I have seen many examples of other models for how we could live in the archives. Some are alternatives that haven't come true. The point is, we don't have to do it all over again.

We get to learn from time-spatial elsewheres and may choose how to continue the never-ending work, differently, and maybe more positively, under somewhat different circumstances. This is the only

way democracy might be able to function sustainably. I believe that co-operative practices light the way.